There is an old saying in the investment world that “Profits are an opinion, but dividends are a fact.” The implication is that nothing matters until an investor has received her cash distribution. It may therefore seem reasonable to focus on the dividend yield as a proxy for return. However, a stock investment has two return components: price appreciation and dividends. An investment strategy which over-relies on dividends and neglects future appreciation will likely result in poor portfolio construction and sub-par investment returns.

Several developments have lessened the importance of dividends to stock market returns over recent decades. One key event occurred in 1982 when the Securities & Exchange Commission (“SEC”) provided a “safe harbor” for companies buying back their own shares under Rule 10b-18. Prior to that ruling, share repurchases were viewed as a form of illegal market manipulation. The evolution took some time, but the SEC ruling has had a meaningful influence on corporate finance. Whereas in the prior era public companies would provide “shareholder payouts” only through dividends, the new paradigm enables management to deliver them via dividends and/or share buybacks. All things being equal, share buybacks reduce the amount of stock outstanding counted against earnings, thereby increasing Earnings Per Share (“EPS”). A primary buyback benefit versus a dividend is that it is not a taxable event; an investor can control the timing of selling appreciated stock to incur capital gains taxes. Berkshire Hathaway was a pioneer in never paying a dividend; Warren Buffett has recommended its investors pare their holdings, and incur taxes, if they need cash.

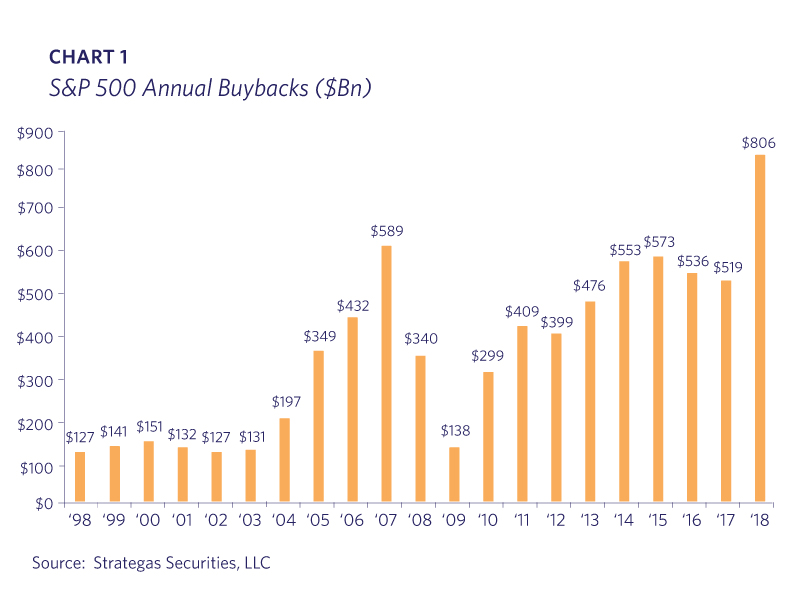

Stock buybacks not only lower a company’s outstanding share count, but also create incremental demand for the stock. Both actions put upward pressure on the company’s stock price. Since modern executives are often handsomely paid in their company’s stock, a cynical view of stock buyback plans is that they are purely a way to enhance the take-home pay of the people authorizing them. There is undoubtedly some truth to this argument, but it is comforting to know that the interests of the executive team are aligned with investors. The use of share repurchases has exploded in recent years as a means of returning capital to shareholders. 2018 was a record year due to the strong economy and the cash repatriation enabled by the December 2017 Tax Reform bill (Chart 1).

Regardless of management’s motivation, the impact on individual stocks can be profound. For example, over the past five years Honeywell, Visa, and Home Depot have reduced their shares outstanding by 7%, 13% and 19%, respectively. In the case of Home Depot, the reduction in shares outstanding increased EPS from $7.90 to $9.73. At a 19x P/E multiple, this is the difference between Home Depot’s stock trading at ~$184 versus ~$150 per share. The Wall St. Journal reports that 25% of the S&P 500 added at least 4% to their EPS through buybacks during 2019’s first quarter.

Another development was the emergence of the institutional Venture Capital industry in the 1970s, and the episodic supply of emerging growth companies entering the public markets via IPOs thereafter. A new “small- cap” asset class was created, particularly in the technology industry. These fast growing companies didn’t pay dividends because they were either unprofitable or were heavily investing in their future. Silicon Valley culture regards dividends as an admission that a company’s growth days have abated, and that it is no longer an entrepreneurial enterprise; the rationale is that the high-growth company can generate better returns by reinvesting retained capital than the shareholder can with the dividend.

Today we see this entrepreneurial culture not only at small, emerging growth companies, but in their mega-cap brethren as well. There are numerous large-cap digital and software businesses disrupting and conquering industries including retail, financial services, technology, media and advertising. With major industries in upheaval and market share shifting to the new entrants, the massive opportunity has encouraged executives to continuously invest in the business rather than pay a dividend. Mega-cap companies such as Alphabet, Salesforce, Adobe, Amazon, and PayPal plow their ample cash flow back into growth, new initiatives and M&A. Google acquired YouTube while Facebook bought its two fastest growing social media properties, WhatsApp and Instagram, for what are now seen as bargain prices. These companies continue to deliver high-margin revenue growth at rates that far surpass their legacy competitors. Many are viewed as having broad competitive moats in “winner take all markets,” and investors have rewarded their reinvested retained earnings with high valuations.

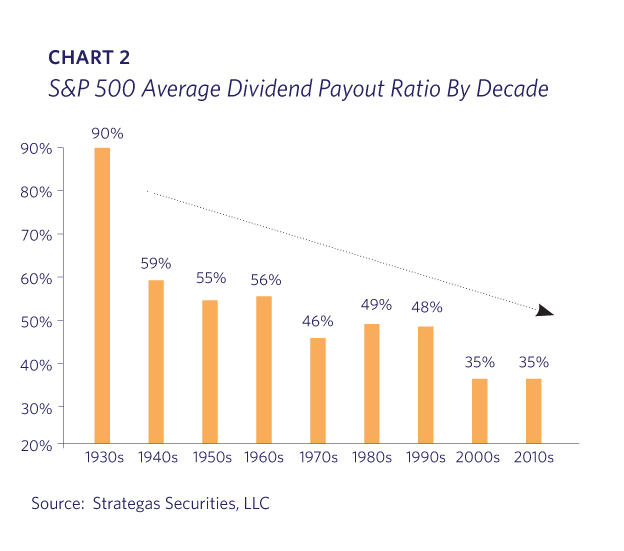

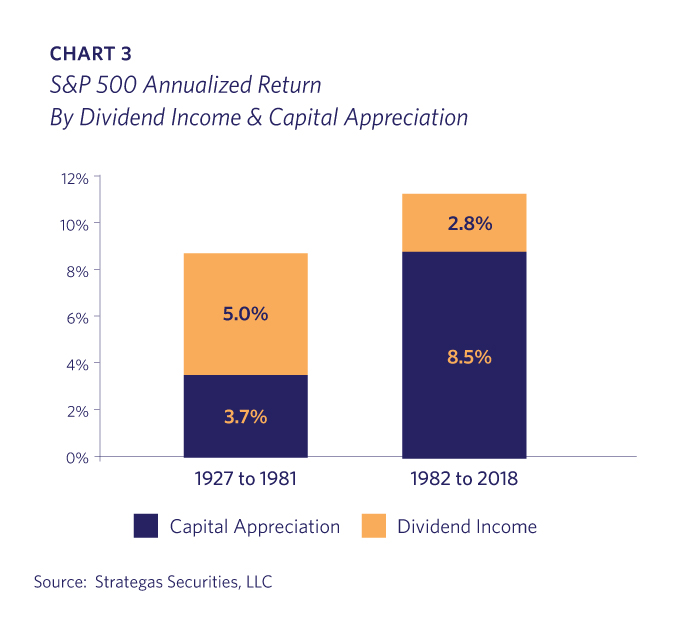

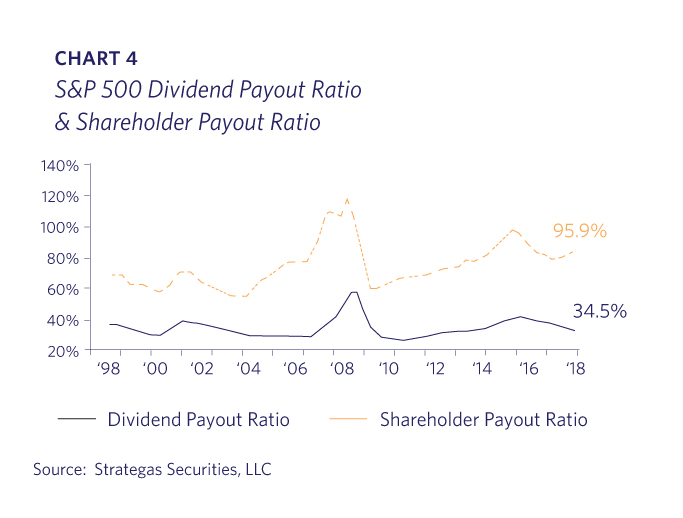

The previously cited developments have substantially changed the stock market landscape. The dividend payout ratio, which is defined as the amount paid in dividends as a percentage of net income, has steadily declined over many decades (Chart 2). Since 1982, dividend income has accounted for only 25% of stocks’ total annualized return versus its 60% contribution from 1927 through 1981 (Chart 3). An investor with the intention of “clipping coupons” via dividend checks is likely to fall far behind. However, stock buybacks can also be viewed as a way to return capital to shareholders. A traditional view would define the S&P 500’s shareholder capital return as the current 34.5% dividend payout ratio, but by adding buybacks to dividends in the shareholder payout calculation the capital return is a far more generous 95.9% of earnings (Chart 4).

In today’s world companies with higher dividend yields are typically growing slowly and have more limited investment opportunities. In fact, their shareholder base requires a higher dividend in order to justify owning the stock. These stocks are often owned as bond proxies ñ with the hope its stock price will hold steady while the company continues to maintain its dividend; Coca-Cola would be a good current example. A high dividend may also signal the market’s skepticism about the stock sustaining its price level and/or its ability to maintain the pay-out; for example, AT&T’s stock has dropped over 25% in the past three years and is now offering a 6.5% dividend yield, which indicates the market’s lack of confidence.

Lyell Wealth Management is a “total return” investor. We like dividends as much as the next investor, but we operate in a world in which many of the most innovative and leading companies pay negligible or no dividends. We also know that state-of-the-art corporate finance uses share buybacks in combination with or instead of dividends to return capital to stockholders. This means that dividends matter less than they did prior to 1982, and a high dividend may signal poor prospects for the company in question. An investor ignoring the modern-day disruptive, “blue chip” global leaders would have trailed the stock market indices by a large margin in recent years and will likely continue to do so going forward. We tend to rely more on non-equity asset classes, such as fixed income and private real estate, to generate cash flow and reduce portfolio volatility. For the equity allocation, an investor must seek out stocks that can appreciate over time in order to participate in broader market returns.